If you’ve read my blog post about Bart Van Es’s biography The Cut Out Girl, you’ll know that during World War Two, The Netherlands (Nazi-occupied at the time) was so efficient at rounding up its Jewish population, that the death rate was the highest in Europe, higher even than in Germany. I highly recommend Van Es’s book. But the definitive account of the Dutch-Jewish experience under the Nazi regime is arguably Anne Frank’s diary.

Of course, I’d known about the diary of Anne Frank from when I was young. How could I not? Since it was first published in 1947, it’s been read by tens of millions of people around the world. It’s taught in many UK schools and is required reading in schools in Holland (so I’m told). During teaching practice, I’d even used extracts of it as an example of diary writing style. But I’d never read the whole thing so when I visited Amsterdam last month, I decided to commemorate the trip by filling the Anne-Frank-sized hole in my life.

My question was this: why did her diary become so iconic? There are other contemporaneous accounts of Nazi-occupation – Anne’s story would have been replicated in Germany, Hungary, Poland, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, and Italy (and the ‘Kindertransport’ is rightly remembered as a significant humanitarian rescue of Jewish children) – so why this above all others?

Well, for start it’s instantly engaging. Anne writes her diary as though she’s writing letters to her best friend, ‘Dearest Kitty’. (It just so happens my oldest friend calls me Kitty, so it felt like every entry was addressed to me personally.) ‘I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able to confide in anyone, and I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support.’

And we see Anne change. The first entry is on 12 June 1942, her thirteenth birthday, before the Frank family go into hiding; she makes the last entry on 1 August 1944, aged fifteen, having been in hiding for a little over two years. During that time she grows from being a flighty teenager, writing about her school, her classmates, her ’throng of admirers’, and complaining about her mother, into an intellectually curious but introspective young girl, enjoying a nascent relationship with Peter van Daan, whose family are hiding with the Franks.

And then there is the occasional gut-wrenching sentence, like when Anne writes about losing her fountain pen and concludes it has fallen into the stove and burned. ‘I’m left with one consolation […] my fountain pen was cremated, just as I would like to be some day.’ Oh, Anne.

Anne wanted to be a journalist or a writer. ‘I know I can write. A few of my stories are good, my descriptions of the Secret Annexe are humorous, much of my diary is vivid and alive, but…it remains to be seen whether I really have talent.’

Anne achieved her ambition. Just not in the way she expected.

Of course, the diary’s main emotional grip lies in what Anne can’t record. Three days after the final entry, the Annexe was raided and its occupants arrested. The following month Anne was sent to Auschwitz and from there to Bergen-Belsen. It is understood she died of typhus in March 1945, about six weeks before the camp was liberated by British soldiers.

Rating: ** Worth reading

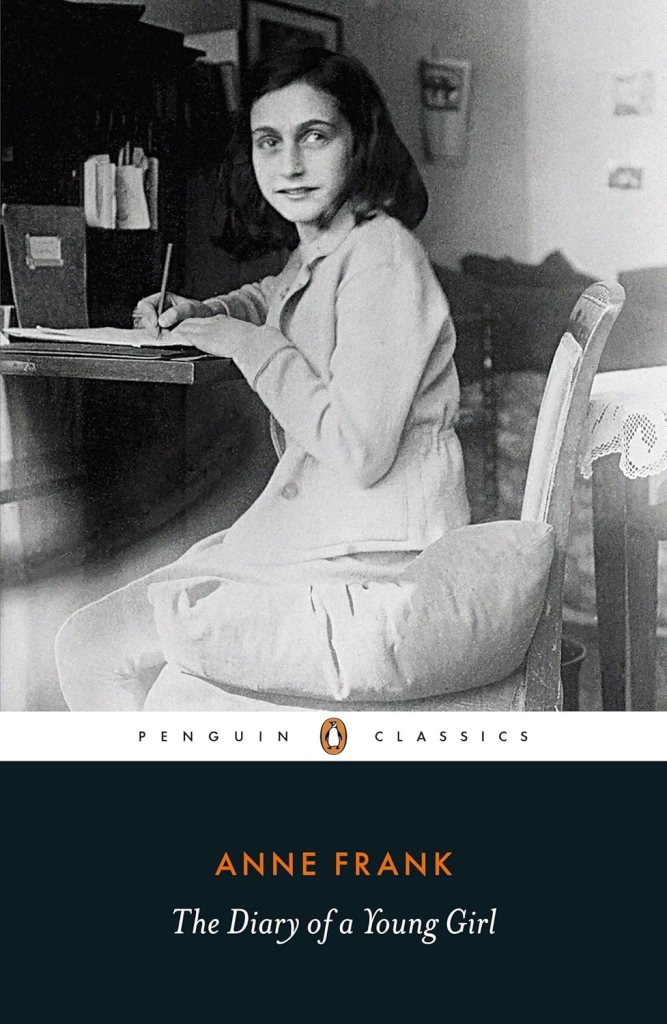

PS I read the Penguin Classics edition of Anne’s diary. The Forward explains that there are actually three versions of the diary: Anne’s original diary (version a); a second diary, which was an edited version of the original – Anne had decided to publish a book based on her diary after the war was over so she began rewriting it (version b); and the diary as it was published by her father after the war, which was shorter, and combined passages from version a and version b (version c). My Penguin Classics edition is based on version b.